Corn harvest is well underway in Illinois and we should move through our harvest at a decent rate given the current forecast. It is at this time every year that we start to see more images of mature, senesced plants and plant parts with individuals curious about, “what infected my plant” often in an effort to determine why the field may be underperformining in some manner. Sadly, once plants have matured, it is nearly impossible to determine: 1) What pathogen infected your corn or was actually responsible for the yield impact, and 2) If the disease actually impacted the crop. Why is this the case?

- Many microbes love senescing or dead tissue. Many microbes, for example, Fungi, can obtain nutrition from dead or dying plant parts. In fact, many fungal pathogens produce toxins partially as a means to kill plant tissues and acquire nutrients. On the other hand, many non-pathogenic fungi can also rapidly colonize dead and dying plants. In a situation where a plant is totally dried down, it is often very difficult to distinguish or isolate pathogens from leaves due to contamination of dead tissues by numerous fungal species. A similar case can be made for root and stalk rots. As the plant matures, numerous fungi can colonize roots and stalks, and colonization by saprophytic fungi may give the impression that there was a yield-impacting effect when this may not be the case. There are some exceptions to these, “rules.” For example, many obligate pathogens (rusts, tar spot) produce defined spores or structures that can be identified by an experienced individual.

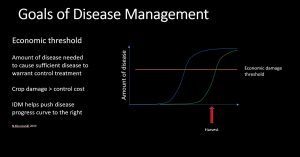

- The capacity for a disease to impact the crop involves many factors, but in many cases, when the disease arrives is as or more important than what disease arrived. Diseases that are active during critical periods of grain fill are more likely to result in significant yield losses than diseases arriving late in the season, when yields are nearly made. A great example of this is evident in Southern rust, where if the disease arrives prior to R3, fungicide applications are likely to be an economically sound investment, whereas arrival near R5 is unlikely to cause sufficient disease to reduce yields or impact standability. In those cases, fungicide applications might reduce disease development but the benefit in terms of yield protection is unlikely to be sufficient enough to cover application costs.

These two points highlight the main take home message: scout your fields during the season, every 1-2 weeks from V6-R5. Scouting helps you determine when and what is developing in your field, enabling you to make informed management decisions and improve your overall bottom line. In addition, scouting can help reduce surprises come harvest. Yes, it is Halloween, and many people enjoy a good scare, but I’d rather see that happen to you while watching a scary movie as opposed to when watching the grain monitor.