Every year we hear about fungicides, and their utility in agronomic production systems. Indeed, these products can be an extremely useful tool to prevent yield-related losses resulting from fungal diseases. However, reduced commodity prices are making it crucial for producers to minimize inputs in order to maximize profits. Fungicides can be near the top of the list when producers are deciding on what inputs to exclude during the season. Determining if an application is warranted can be a difficult decision to make.

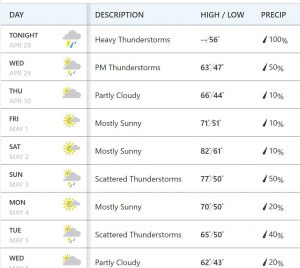

Before I go further, I need to circle back and discuss plant diseases, and how they work. Unfortunately this means I need to utilize the disease triangle or pyramid, which we all have seen innumerable times during discussions of plant diseases (Figure 1). It does a great job of illustrating how diseases work, which is why it is utilized so often.

The Disease Triangle (Pyramid)

- Plant diseases are caused by pathogens. In order for a disease to occur, the correct pathogen (species, race, pathotype) must be present, and at the correct growth stage to infect the plant.

- A given pathogen can only infect a susceptible host plant. This means that the plant needs to be the correct species, lack resistance to the pathogen, and be at the correct growth stage required by the pathogen for infection. Different pathogens may infect different hosts and have different host ranges.

- Disease only occurs under the correct environment. This means that the environment is conducive for the particular disease (temperature, moisture, light). Different pathogens have different environmental requirements for growth and infection.

- The amount of disease is impacted by the amount of time all three points in the disease triangle are met. The longer all the disease requirements are met, the worse the disease, and the greater impacts it may have on crop productivity.

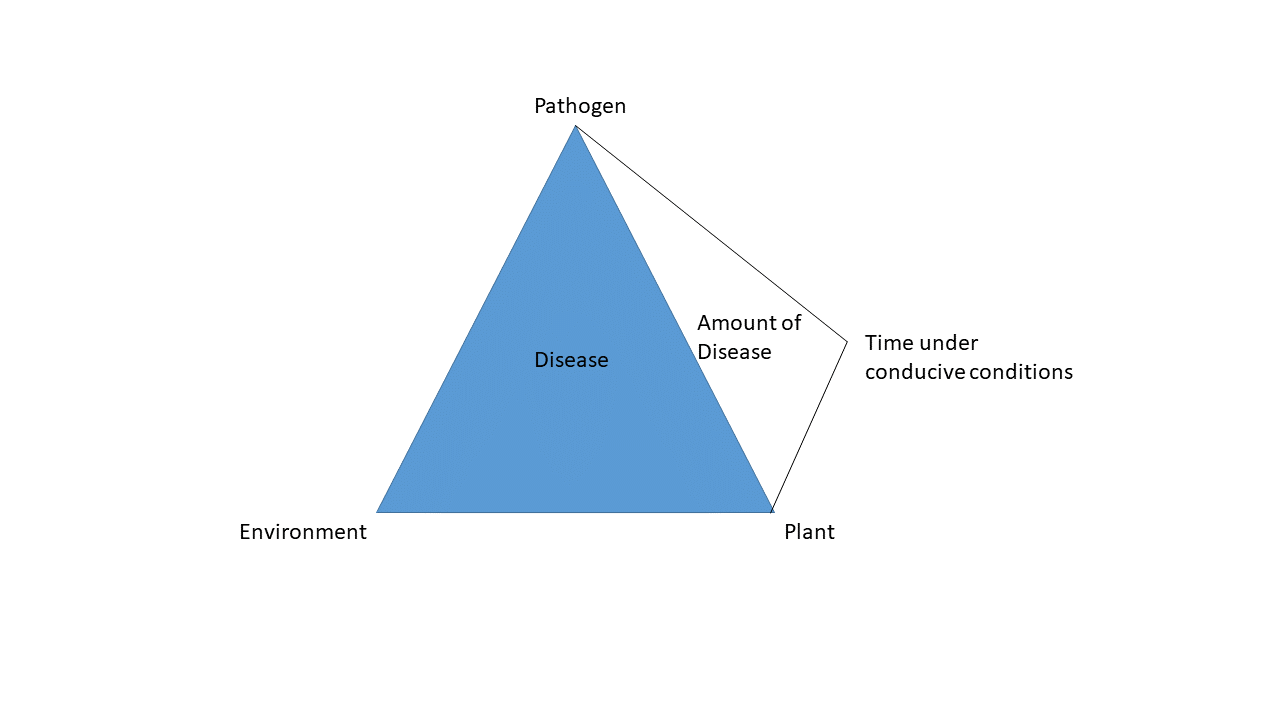

It is also important to note that different crops can handle different levels of disease before yield is impacted. The benefits of making a fungicide application are most pronounced, and you are most likely to see a return on your investment, when it prevents the disease from reaching the economic threshold. This is the level of disease where making a fungicide application will provide an economic return (Figure 2).

Fungicides help to take part of the disease triangle out of the equation, assuming the other parts of the triangle (host, environment) are or will be met within 2-3 weeks of application. If a yield-limiting fungal disease epidemic occurs, the application of a fungicide would help reduce the epidemic and control disease-related losses.

Let’s boil all that down to a couple brief statements:

- Fungal diseases only occur when the correct pathogen, plant host, and environment occur together

- The amount of disease is related to the duration of time conditions for disease are met

- Not all disease results in yield loss

- Fungicides minimize fungal disease

- Economic returns are greatest when fungicides are applied to susceptible plants and conditions favoring disease occur.

Thus, fungicides can minimize disease related yield loss. Any “yield increases or bumps” are related to the level of disease that would have occurred if the fungicide was not applied. Yes, there are some fungicides that can have subtle impacts on plant physiology. Sometimes these effects can have small impacts on plant yield. However, these physiological effects are highly unpredictable. When a fungicide is applied to control a disease, the result is highly predictable, given that a disease occurs. This should be the #1 reason for using a fungicide-reducing the impacts of fungal diseases to mimize yield losses.

Reasons for making a fungicide application decision:

Making a fungicide application decision needs to take in consideration the types of pathogens most often encountered in the field/location, the resistance rating of the hybrid or cultivar you are using to the pathogens most likely to be encountered, and the management practices you implement on that field to help reduce disease over time.

Remember that many diseases such as grey leaf spot on corn or frogeye leaf spot on soybean, are predominantly residue borne. Any practices that help reduce local inoculum buildup, for example, crop rotation and tillage, helps to degrade that residue and reduce pathogen populations, such that the amount of potential disease is reduced. Utilizing these practices helps to push the curve further to the right, in the case of Figure 2, resulting in a population that takes longer to reach a level where yield loss would occur. If you do not rotate and use no till or minimal tillage systems, that residue remains on the surface and these pathogens can build up.

I like to use the idea of a risk ladder when it comes to deciding on the likelihood that a fungicide will be needed in a particular field before planting. The more items on this list that are a “Yes” on the ladder the greater the disease risk.

Fungal foliar disease risk ladder

- Planted a susceptible cultivar/hybrid to common diseases _______

- Do not rotate field among crops _______

- Do not till field _______

- History of fungal foliar disease _______

- Irrigate _______

During the season, other factors can increase risk. For example, heavy rains can promote disease. In the case of diseases that are not residue borne, but blow in from other regions, such as Southern rust on corn, the presence of the disease in nearby regions may increase risk. Perhaps the environment has been very conducive to disease, and disease has started early in the season? How high are you on the risk ladder?

This leads me to my last point regarding making fungicide decisions: conduct your own research. With all the money you are putting into your crop, it makes sense to invest a little extra time to determine if your decision was a good one. That knowledge can be used to help you make more profitable decisions in subsequent seasons.

There are many different ways you can do on farm trials, and they can range from extremely simple to complex. Even a simple test can provide useful information. Regardless of if you want to do replicated strips and calculate statistics, or simply want to split a field, it is important to always include an untreated strip. Without an untreated strip, you cannot draw conclusions if you do not see a difference. You also have no idea of the amount of yield that was protected by the application of the fungicide.

For example, if you want to look at two products and split the field in half, what happens if you see no yield difference between the field sections? Is it because the products are equal or because there wasn’t enough disease to cause a yield reduction? A single untreated check can provide you a basis for making conclusions regarding the application of a fungicide to a particular field.

When you include a strip, make sure it runs through a representative part of the field. Do not locate it near field edges or unrepresentative parts of the field. Make sure the strip is wide enough so you can determine yield. The more tests you run with an untreated strip, the more confidant you will be in making fungicide application decisions in the future.