2019 was certainly a year we are all looking forward to wrapping up, and many are starting to do just that throughout the state. Our lab started harvesting both beans and #corn about a week ago and on my trip today I saw several combines cutting corn and beans.

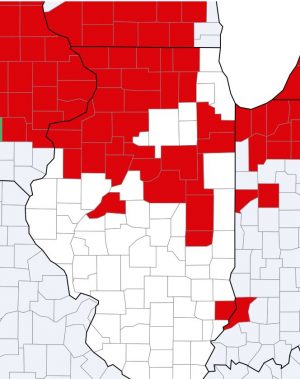

As I mentioned last year, tar spot has made annual appearances in Illinois since it’s initial detection in 2015. Last season, conditions that favored disease development and spread allowed the tar spot fungus, Phyllachora maydis, to develop to a significant degree well before the crop had matured, and many saw significant losses. To add further insult to injury, the conditions that favored tar spot also favored other, more commonly encountered diseases including grey leaf spot, ear rots, and several types of stalk rots. The end result was a huge mess in the Northern part of the state, and many concerned producers.

This season, the overall incidence of tar spot is similar to last year in #Illinois, but the severity of the disease is significantly lower. In many parts of the state where tar spot has been detected it did not reach noticeable levels until the last 10-14 days, and in most cases corn in these areas is well past R5. Why was tar spot less severe this year?

We can speculate on several reasons. First, remember the disease triangle? Disease only develops when you have a susceptible host, appropriate pathogen, and conducive environment. This year we ran into a period of hot and dry conditions for a significant period of time in parts of the state where tar spot was severe last year. If you recall, we were close to a drought in parts of the Northern and East-central Illinois when many fields were hitting that crucial VT/R2 growth stage. The combination of the heat and dry conditions could have delayed the onset of tar spot, resulting in disease developing later in the season and to a lesser degree than in 2019. It is important to remember that onset of disease relative to the growth stage of the crop is critical in determining overall yield impact. When disease arrives early in crop development yield impacts are increased compared to disease arriving later in the season.

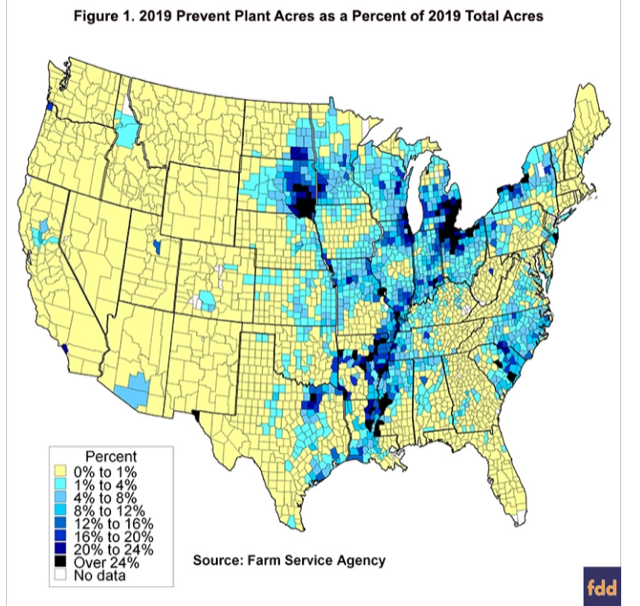

Second, the disastrous late start to the season resulted in a significant amount of prevent plant acres. Phyllachora maydis is an obligate pathogen, meaning that it needs a living host to grow and reproduce. Fewer acres of corn planted likely resulted in less overall inoculum at local levels. Tar spot is polycyclic, meaning that it can continue to infect and produce more inoculum (spores) as long as conditions are favorable. New spores can be dispersed, infect susceptible corn, and within 2-3 weeks, produce more spores. With fewer acres of corn planted, this means that there was less host material for the fungus to grow and multiply, and subsequently, less inoculum to cause disease.

A third potential reason could have been related to winter conditions from 2018-19. If you recall, we had several periods with freezing conditions, commingled with abnormally warm periods. We know that P. maydis can overwinter within the dark stromata (tar spots) on infected residue. However, these temperature shifts may have impacted fungal physiology and dormancy, reducing potential survival of the fungus.

That being said, what does the 2019 tar spot situation mean for 2020 corn? One cannot be certain, but for the reasons highlighted above, we would expect less P. maydis inoculum to overwinter, simply due to fewer corn acres planted and less corn infection in 2019. This could result in lower inoculum loads and potential disease in 2020. It will be interesting to see what happens next year. In the meantime, keep up the great work scouting, send any tar spot samples to the UIUC plant clinic or myself (email, phone, twitter) and let’s look forward to a productive 2020.